To be sure, teaching in China is not the kind of thing you do to make your friends back home jealous. I’ve made it half way across the world: from New York, where I was born and raised, to  Austin, Texas where I got my Master’s degree and bought and sold my first two houses during a budding career in publishing, to New Zealand where I ran away from said budding career to learn how to farm sustainably, to Thailand where I taught English for the year that should have lasted a lifetime, to India where I learned the actual taste of food poisoning. Two years after leaving America, I now find myself in Guangzhou, China, musing over past adventures, and daydreaming of ones that await.

Austin, Texas where I got my Master’s degree and bought and sold my first two houses during a budding career in publishing, to New Zealand where I ran away from said budding career to learn how to farm sustainably, to Thailand where I taught English for the year that should have lasted a lifetime, to India where I learned the actual taste of food poisoning. Two years after leaving America, I now find myself in Guangzhou, China, musing over past adventures, and daydreaming of ones that await.

The largest city in China’s southern province of Guangdong, Guangzhou is home to more than 12 million residents and migrants who come from all over China (and the world) to work. The famed Silk Road has extended from Guangzhou to Alexandria, Egypt all the way back to the Byzantine Empire more than a thousand years ago. Funny, though, as I hadn’t heard of it before being offered a position to teach English at a private language institution via a Skype interview in a dusty cyber café in India before my tabla lesson along one of the ghats in holy Varanasi. With a three-month Indian Tourist Visa about to end, and two positions open for my partner Ben and I, we took the jobs in China, without even being able to pronounce the city where we were to work and live for the next year. “Is it Gwang-zjoe? Or Gwong-zhoo?” I remember asking, as Ben Wikied China’s third largest city, after Shanghai and Beijing.

I’ll admit that the wide, tree-lined streets from the Guangzhou airport to our downtown hotel was a refreshing respite after months in India sidestepping cow dung and avoiding hurried tuk  tuk drivers. Within the first week of being here, I met traders, factory managers, translators, TV personalities, DJs, and English teachers from Colombia, Venezuela, Israel, Russia, the UK, Canada, Mexico, South Africa, Australia and the good ol’ USA at a house party on the 16th floor of a new skyrise building in downtown, Guangzhou. Within two weeks, I would be living in the same building

tuk drivers. Within the first week of being here, I met traders, factory managers, translators, TV personalities, DJs, and English teachers from Colombia, Venezuela, Israel, Russia, the UK, Canada, Mexico, South Africa, Australia and the good ol’ USA at a house party on the 16th floor of a new skyrise building in downtown, Guangzhou. Within two weeks, I would be living in the same building, on the 19th floor. When my best friend back home told me her visions of me peering out of my window and being surrounded by trees, I sent her this message: “I’m sending you some photos taken from our apartment balcony. It’s China at its finest, really, as it’s just boxes and boxes of people stacked high into the sky ‘cuz they can’t all fit on the ground floor.”

So what exactly is it that I’m doing here? I ask myself this on a daily basis, actually. Primarily, I’m teaching English to a few hundred weekend and nighttime students who are anywhere from 3–18 years old.

Sometimes the younger students draw poop on the whiteboard, but the teenagers sometimes have compelling insights about the world. I taught a “VIP” (one-on-one) class with a 15 year old  recently who had traveled to Australia, the US, Thailand, and Japan. Instead of sounding like the typical spoiled and entitled teen whose parents could afford to send her abroad for the holidays, she offered thoughtful comments about how citizens abroad are caring and considerate. She had read a story in the news about a two-year-old girl who died in China after a hit-and-run accident that happened in broad daylight. As she re-enacted the story by standing up, pretending to drive, and then pretending to be run over, she dropped to her knees and was filled with anger and confusion as to how someone could possibly hurt another person and continue driving as though nothing had happened. She shook her head and told me in despair that dozens of people walked by the little girl and no one helped her. In other countries, she was sure, this would not happen. I hesitated in telling her that people have died, ephemerally unnoticed, in hospital waiting rooms in America. Instead, we read about the Rights and Responsibilities of Canadian Citizenship, whereby citizens are required in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms to help others in the community. This made her feel better and hope to immigrate to Canada some day.

recently who had traveled to Australia, the US, Thailand, and Japan. Instead of sounding like the typical spoiled and entitled teen whose parents could afford to send her abroad for the holidays, she offered thoughtful comments about how citizens abroad are caring and considerate. She had read a story in the news about a two-year-old girl who died in China after a hit-and-run accident that happened in broad daylight. As she re-enacted the story by standing up, pretending to drive, and then pretending to be run over, she dropped to her knees and was filled with anger and confusion as to how someone could possibly hurt another person and continue driving as though nothing had happened. She shook her head and told me in despair that dozens of people walked by the little girl and no one helped her. In other countries, she was sure, this would not happen. I hesitated in telling her that people have died, ephemerally unnoticed, in hospital waiting rooms in America. Instead, we read about the Rights and Responsibilities of Canadian Citizenship, whereby citizens are required in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms to help others in the community. This made her feel better and hope to immigrate to Canada some day.

To see what it’s like working as a teacher at EF English First in Guangzhou, China, check out this video I made for the school:

Find more videos like this on EF English First Teachers

Another one of my teenaged students scored the highest in the entire province of Guangdong on a high-school entrance exam, which determines placement into a top high school. His  mother passed along a message of thanks, though I felt it should go to her son instead of his weekend English teacher. Modesty aside, I am proud to contribute to Nate’s ability to remember past tense verbs.

mother passed along a message of thanks, though I felt it should go to her son instead of his weekend English teacher. Modesty aside, I am proud to contribute to Nate’s ability to remember past tense verbs.

Pride is something rare that I feel here; however, more often than not I tend to feel claustrophobic in this city with so many commuters shuffling back and forth on foot, by bus, bike, fancy car, or on the metro. Usually jam-packed among people in train cars and in elevators, there have been fewer times in my life where I thought I was actually going to die from suffocation or worse (a Slipknot concert in my heyday came close). And for some reason (and especially when I’m in a hurry), people here have a tendency when “walking” to stop short right in front of me to stare at the sky or have a think about where they want to go next. Multiply that by 10 people doing the same thing all around me at any given time, and it makes for a very indirect commute to just about everywhere—the grocery store, down the sidewalks, or when trying to cross the street while avoiding cars who seem immune to red lights.

The bright side of being in such a densely packed city is that I am exposed to a large amount of culture in a small amount of time. Not a single day has passed where I’m not met by some new cultural phenomenon that makes my eyes widen. The one that still boggles my mind is the bare-crotch pants that toddlers here wear. Instead of diapers, babies’ behinds are exposed to the wind to prevent any wasting of time if they need to expel right in the middle of the street, or in a garbage can behind my lunch table, as was the case last week. Parents and grandparents just lift the toddlers up, and give them a little squeeze as though they were a water bottle. When I first got here, I would see chunky brown spots on the sidewalks and assume some drunk had upchucked his libation, but within a few months, I started to see parents allowing their babies to “go” on sidewalks, through holes in the ground, or anywhere they may need to go that just  happens to not be a bathroom.

happens to not be a bathroom.

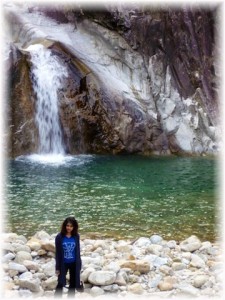

When the intensity of people and their publically pooping babies hits a climax, it’s usually time to head out of Guangzhou. So far, we have been to “China’s Hawaii,” which is a large island called Hainan just south of the mainland. Our journey happened during the monsoon season, which meant that a typhoon arrived on the island at the same time as our airplane. This resulted in massive floods throughout the streets and the boardwalk of the beaches in Sanya buckling underneath the weight of itself. Another time, we tried to visit a national park with karst mountains 88KM west of Guangzhou and ended up being kidnapped by a taxi driver who drove us in the wrong direction for an hour and a half and refused to turn around or let us out of the car until we paid his hefty 568RMB ($92 USD) fare. Those nightmare situations were  tempered by other, successful, trips to Nanling National Park in Ruyuan where I’ve never seen so many beautiful and pristine waterfalls leaping off of mountain edges, and Yangshuo , which is an absolutely beautiful and magical tourist-friendly city with international candle-lit cafes, motorbike and bicycle rentals, river rafting, mud caving, rock climbing, and friendly locals. Driving on our rented motorbike in Yangshuo left us sunburned and grinning for days. We drove up and down the mountainous hills, staring out onto the layers and layers of karst mountains that dipped high and low along the horizon. We hiked up Moon Hill to see the giant hole in the side of the mountain. And on our descent down, we couldn’t help but laugh when the dozens of Chinese student tourists moaned about climbing up the stairs in their shiny, new Adidas. When we made it to the bottom of the mountain, a nice older Chinese woman asked us if we wanted to eat, by motioning her hand to her mouth. On a high from such a spectacular view, I told her yes and proceeded to cross the

tempered by other, successful, trips to Nanling National Park in Ruyuan where I’ve never seen so many beautiful and pristine waterfalls leaping off of mountain edges, and Yangshuo , which is an absolutely beautiful and magical tourist-friendly city with international candle-lit cafes, motorbike and bicycle rentals, river rafting, mud caving, rock climbing, and friendly locals. Driving on our rented motorbike in Yangshuo left us sunburned and grinning for days. We drove up and down the mountainous hills, staring out onto the layers and layers of karst mountains that dipped high and low along the horizon. We hiked up Moon Hill to see the giant hole in the side of the mountain. And on our descent down, we couldn’t help but laugh when the dozens of Chinese student tourists moaned about climbing up the stairs in their shiny, new Adidas. When we made it to the bottom of the mountain, a nice older Chinese woman asked us if we wanted to eat, by motioning her hand to her mouth. On a high from such a spectacular view, I told her yes and proceeded to cross the  street and follow her into a dense path of bushes and shrubs. Ben wondered where we were going, but I was ready to follow this nice lady wherever she wanted to lead us. Turns out she had a family restaurant in her backyard that looked right at Moon Hill. Being pescetarian in China is a little hard to explain sometimes, so when I said “Wo boo yao roe,” which is about the only thing I can say in a Chinese eatery and translates to “I don’t eat flesh or meat,” she brought me into her family kitchen and had me point to what I wanted to eat. Some bell peppers, chilies, mushrooms, onions, garlic andddd a bit of cabbage will do, thank you. She told her mom and four sisters what I wanted and went over to their wok and threw it all together into a beautiful, spicy dish. The woman who brought us over to her restaurant sat and chatted with us in what little English she knew and we did the same with our pithy Chinese. She said she

street and follow her into a dense path of bushes and shrubs. Ben wondered where we were going, but I was ready to follow this nice lady wherever she wanted to lead us. Turns out she had a family restaurant in her backyard that looked right at Moon Hill. Being pescetarian in China is a little hard to explain sometimes, so when I said “Wo boo yao roe,” which is about the only thing I can say in a Chinese eatery and translates to “I don’t eat flesh or meat,” she brought me into her family kitchen and had me point to what I wanted to eat. Some bell peppers, chilies, mushrooms, onions, garlic andddd a bit of cabbage will do, thank you. She told her mom and four sisters what I wanted and went over to their wok and threw it all together into a beautiful, spicy dish. The woman who brought us over to her restaurant sat and chatted with us in what little English she knew and we did the same with our pithy Chinese. She said she  lived in the house with her sisters and mother and that they ran the restaurant together. I looked around at her garden patch and saw that they grew everything we had on our plate, which made it extra delicious. I have read that a small portion of China is fortunate to have food grown in clean soil free from industrial contamination, Hainan being one of these lucky places. I have also read about 50% of wine in this county is counterfeit, poured into an old bottle, slapped with a fake label, and made from toxic methanol instead of beverage grade ethanol—some of the “wine” doesn’t even contain grapes. It’s difficult to know what you’re putting in your body when wining or dining here.

lived in the house with her sisters and mother and that they ran the restaurant together. I looked around at her garden patch and saw that they grew everything we had on our plate, which made it extra delicious. I have read that a small portion of China is fortunate to have food grown in clean soil free from industrial contamination, Hainan being one of these lucky places. I have also read about 50% of wine in this county is counterfeit, poured into an old bottle, slapped with a fake label, and made from toxic methanol instead of beverage grade ethanol—some of the “wine” doesn’t even contain grapes. It’s difficult to know what you’re putting in your body when wining or dining here.

We have six more months to make use of our Chinese visa, which is something I never anticipated I would have in my passport. I will see Tibet before I leave this country, even if booking that trip will literally melt my wallet. I’m over the one-month honeymoon phase, and the third-month alienation stage of culture shock when all I did was eat sandwiches and avoid Chinese culture. I’m finally embracing the culture and trying to accept it. Who knows, maybe before I leave this place, I’ll learn to love it. As with all things in life, no one knows until it happens. Here’s to accepting it all …

Read more about Suzanne’s travels and experiences at www.suzannemahadeo.com.